Towards a Relational Theory of Copyright Law

Carys J. Craig

Carys J. Craig, LLB (Hons), LLM, SJD, Associate Professor of Law, Osgoode Hall Law School, York University, Toronto, Canada

2011 288 pp Hardback 978 1 84844 839 1

Hardback£65.00on-line price £58.50

As the synopsis of this book said it argued “that the dominant conception of copyright as private property fails to adequately reflect the realities of cultural creativity” it sounded to me as if this might be a pleasant change from much of the copyright lip service that gets written in academic circles.

So, let’s see how I got on when I started reading between the covers.

1. Introduction (download)

Funnily enough, even before reading the first sentence, my eye is caught by a revelation in the acknowledgements on the preceding page that Carys Craig previously published “Locke, Labour, and Limiting the Author’s Right: A Warning Against a Lockean Approach to Copyright Law“ (2002) 28 Queen’s Law Journal 1-60.

“Oh oh!” is my first thought. An author ‘Against a Lockean approach’ does not bode well.

The first paragraph inoffensively summarises our cultural predicament, but the 2nd paragraph which starts “Copyright law, which creates exclusive rights over intellectual expression, is one such regime” is the first thing that is a little too blithe for my liking. One should find immediately suspect the phrase ‘creates exclusive rights’, since, as we know, rights cannot be created by law.

So what does Carys think copyright is?

“Fundamentally, copyright is no more than ‘the right to multiply copies of a published work, or the right to make the work public and still retain the beneficial interest therein’”

Au contraire. We have a right to multiply copies of a work by nature. Copyright is law that annuls this right to leave it, by exclusion, in the hands of a few – privileged holders of our right to copy. This is why the term ‘holder’ is used (held in the hands of another). If it was the natural right there wouldn’t be any ‘holding’ about it. We don’t hold a right to our own lives, nor do we hold a right to our own privacy. We have the rights we are born with – we don’t hold them. We have the right to copy as much as we have the right to learn or to teach. Only unethical law can state otherwise, that a right we are born with is to be annulled for the benefit of the few to be favoured or privileged.

The author, originating their work in their private possession, has the natural right either to exclude others from it, or to deliver it to all and sundry, to thereby publish their work, but this is irrespective of any privilege. An author does not need a privilege in order to publish their work. A printer needs a privilege in order to prevent others competing with them in printing copies of a published work.

“From a utilitarian or instrumental perspective, the exclusive rights that copyright grants are justified as a means by which to maximise cultural production and exchange by encouraging the production of intellectual works.” Production is encouraged only according to the myth or revisionist pretext that has this as the primary motive for the Statute of Anne. As for justification, utilitarianism has no problem sacrificing the rights of the individual for the ‘greater good’ (aka the interests of the state), so to suggest that privileges such as copyright can be ‘justified’ in those terms insults the justice that recognises individual rights first, and the state second.

Carys Craig states “The overarching theme of this book is the need to discard notions of natural right, individual entitlement and private property in copyright theory, …” Ouch. The problem with this is that copyright has already discarded these notions. Copyright annuls the individual’s natural right to copy. Copyright disregards the individual’s natural, primordial entitlement to cultural liberty. Copyright abridges the individual’s privacy in forbidding infringement even within it. Copyright even elides the fact that it is the individual’s natural right to privacy that gives rise to the exclusive right to their writings, not the granting of the privilege (which insinuates the natural foundation of privacy as legitimacy for the reproduction monopoly extending it into the public domain). So, I suspect that Carys Craig has swallowed the myth that copyright is a natural right or is a consequence of it.

The introduction does not bode well. I worry to proceed.

2. Constructing authorship: The underlying philosophy of the copyright model

Carys Craig well and rightly deconstructs a prevalent notion of author as creator ex nihilo, but still appears to see copyright as a moral defence of this, i.e. a right against imitation. However, copyright was not created for this. It is simply a commercial defence against unauthorised printing/reproduction (of copies or substitutes). This ties in with the prevalent notion that copyright is intended to prevent plagiarism, when it is simply a reproduction monopoly unconcerned with authorship or accuracy in attribution. As to imitation, one can imitate any other author (via their copyright protected works) as much as one wants (risking litigation only when distributing/communicating). However, if the copyright holding publishers of imitated & imitating works come to a commercially agreeable deal, then what the imitated author or their readers think about the imitating work is irrelevant. If the author is offended at being imitated they have to take it up with the copyright holder. Copyright is entirely a commercial privilege devoid of any moral consideration – notwithstanding any legislative lumping together of moral rights with copyright (the annulling of the right to copy).

It is several centuries of royal grant that gave the printers the idea they had a right to printing monopolies, and it is three centuries of a consequently institutionalised monopoly (of necessity arising in each ‘original’ work) that gives authors the idea they have a right to control the use of their work by others. It is not vice versa. Copyright was not created to derogate from the author’s ‘right’ to control their published work in order to serve the public’s interest in receiving it, and a century or so later to one day share and build upon it. Similarly, ad hoc printing monopolies weren’t granted prior to copyright in order that printers could protect the author’s ‘right’ to control who printed their work. We cannot understand the motivations for printing monopolies and copyright in terms of the notions they have engendered in us over the centuries.

So, I fear that Carys Craig mistakes the notions copyright has engendered (or helped perpetuate) as copyright’s basis or misguided mission. I’d suggest that it is only copyright’s supporters that imbue it with an authorial mission. One cannot find such a mission in the legislation itself.

I wouldn’t dispute that the author may have been elevated over the last few centuries coincidentally or as consequence of copyright and book publishing, and this may well lend convenient support to copyright if inveigled as an authorial right, but ultimately copyright was not created to further the author’s interests or protect their rights, nor even the public’s interest in incentivising authorship to promote their own learning as a consequence. One must not confuse purpose with pretext, however much more philanthropically appealing the pretext would appear to be.

“The persuasive force of Romantic authorship makes this an extremely powerful strategy for obtaining and strengthening copyright protection. As such, its function in copyright discourse has altered very little since the occasion of its first deployment in the eighteenth century literary-property debates, where it was an effective ideological instrument used to cloak the economic interests of the booksellers – ‘a stalking horse for economic interests that were (as a tactical matter) better concealed than revealed’”.

Thus Carys Craig must recognise that the Romantic author is not part of copyright’s mission, but used an excuse for it by the monopolist. The last thing the monopolist desires is for the author to be elevated above them within copyright legislation, e.g. to undermine ‘work for hire’ or to be prevented from surrendering their privilege to publishers (reversion is bad enough).

I sense that Carys Craig has failed to recognise that copyright has no sound ethical basis whatsoever, and that this recognition will forever remain out of her reach. Being unable to reach such a conclusion she is forced to ascribe philanthropic motives, aims, or objectives to copyright in order to criticise the legislation’s performance in those terms and to thus suggest that when these criticisms have been remedied, that whatever remains, must logically, however improbably, constitute a just privilege to suspend the public’s cultural liberty.

Despite joining many others who rightly deconstruct authors as producers of purely original work, Carys Craig still concludes that it is the copyright regime (not its supporters and the indoctrinated public) that is wedded to an invalid concept of authorship, instead of to an unethical monopoly (leaving as little as possible to the impotent authors). Moreover, despite paying lip service to the idea of questioning dogma, Carys Craig cannot help but repeat her own dogma that “The societal function of copyright is to encourage participation in our cultural dialogue”. How can Carys Craig uphold such perverse notions when she has just shown us that copyright discourages dialogue? How can participation be encouraged when imprisonment and/or bankruptcy are punishments for any repetition or evolution of another’s speech (to protect the printer’s traditional monopoly over such an act)?

That which encourages participation in our cultural dialogue is an audience of enthusiastic fellow participants engaging in acts of encouragement, e.g. response, cheers, or even payment.

Carys Craig may as well have said that “Prohibiting one person from repeating the words of another encourages discourse between them”. How can anyone let themselves become so brain damaged by copyright indoctrination that they will accept and embrace such statements as logical?

Books on copyright can be divided into four categories:

- Monopolist: “Copyright is a priori good, but needs reinforcing against a delinquent public.”

- Reformist: “Copyright is a priori good, but needs significant reform if it is to realign with its original, philanthropic mission.”

- Neutral: “My analysis/history of copyright”.

- Abolitionist: “Copyright is, and always has been, an instrument of injustice that should be abolished.”

I suspect this book falls into the second category.

3. Authorship and conceptions of the self: Feminist theory and the relational author

Carys Craig indulges in a rather tedious tract of sophistry by way of proposing a better conception of authorship. To me it’s obvious that we all regurgitate everyone else, our ancestors and environment, but if you need to over-intellectualise it, Carys Craig has ably catered for you.

However, she demonstrates again that she has mistaken privileges such as copyright as natural rights when she suggests that ‘rights’ are weapons: “The notion of the relational self challenges the liberal conception of the autonomous individual as an independent bearer of rights to be wielded against others and the state”.

It is the privilege of copyright that is the weapon, and it is wielded by the one entity powerful enough to wield it: the immortal publishing corporation, and wielded against the mortal individual (often on behalf of the state, interested to suppress sedition).

Rights are what the state was supposedly created to protect – especially to protect the individual against the de facto power of the state, e.g. against being tortured (even if guilty of terrorism, let alone suspected to be), or against being imprisoned without public trial by a jury of one’s peers.

Rights are not weapons to be wielded. Rights are natural boundaries of natural beings.

It is privileges that are the weapons. It is privileges that enable private prosecutions against others’ natural liberties that are the weapons – and they are doubly vicious when held by the legislatively spawned psychopaths we call corporations. A human being may hesitate to resort to litigation when begrudging another’s repetition of their words, for they only have one life and one reputation, but a corporation is immortal, impervious and decisive: it sues for profit without compunction. Corporate PR will ‘manage’ any human misery caused.

Carys Craig persistently uses ‘liberalism’ as a pejorative. I don’t know where she got her notion of liberalism from (perhaps Ayn Rand?) but it is a most illiberal one. She acknowledges that liberals recognise rights as innate to the individual, but then undermines this by suggesting that according to liberals “human relations are cast in terms of clashing rights and interests”. Rights do not clash – and cannot clash, by definition. It is true that a burglar may have an interest in violating another’s right to privacy, but then of course this is an interest clashing with a right. The right is simply the name for the equalised individual’s natural boundary, the natural limit of their natural power to repel others (unwelcome).

Perhaps some liberals believe that copyright is innate to the individual (and so diminish the standing of ‘rights’ and ‘liberalism’), but this doesn’t actually change the fact that copyright is a highly illiberal state granted privilege.

Indeed, if individuals had an innate (and magical) ability to prevent others retelling the stories they’d told, or to prevent others singing the songs they’d sung, then copyright would have been law long before the advent of the printing press and royal grants of exclusive control.

Carys Craig further underlines her rejection of natural rights when she says “Property rights are primarily about relations between persons and not the material thing that is owned. Moreover, there is nothing about property rights that make them intrinsic or pre-social: their significance is entirely dependent upon the rules and guarantees of the state.” So, because she mistakes copyright as a natural right and would reject it as such, she must therefore reject all natural rights – in order to ‘re-imagine’ everything (and copyright too) in terms of her new ‘relational theory’.

On this not uncommon basis of ‘natural rights are nonsense on stilts’ the space that is a bear’s cave is not its property without a state, nor is the object that is a wolf’s dinner (despite nature suggesting otherwise). If a state decides that property need not exist, or indeed should not be tolerated, then human beings subject to the state, unlike bears or wolves, will allegedly gladly abandon any primitive instinct to exert their natural power to exclude others from the spaces they inhabit or the objects they possess, indeed will allegedly be happy to abandon any ability to exchange such spaces or possessions and simply adopt a communistic ideal of free sharing.

Resonant with the dogmatic conclusion of the previous chapter Carys Craig drops another clanger when she concludes with a criticism of “Copyright’s failure to adequately recognise the essentially social nature of human creativity”. Copyright could only fail in this if it actually attempted it. It made no such attempt. It only attempted to effectively reinstate the per-work monopolies that the Stationers’ Company had become reliant upon (and so also remedy the surge in sedition that resulted from not renewing the Licensing of the Press Act).

She says “It makes no sense to talk of the author’s natural rights to own the fruits of her intellectual labour”, but of course I’d disagree. I doubt she’d have been too happy if her publisher had told her that she couldn’t claim ownership to the manuscript of this book and therefore could not claim entitlement to anything from them in exchange.

As naturally as a squirrel has ownership over the acorn in its hands, so an author has ownership of the manuscript in his or her hands, as well as the writing upon it – the result of their intellectual labour. Copyright has nothing to do with this natural exclusive right (except via insinuation and allusion).

So, when she then correctly says “Copyright exists only because it is created and defined by the state, and only to the extent that it is enforceable through state mechanisms” it is her misinformed induction that because she incorrectly believes copyright is a natural right granted by the state, authors have no natural right to own the fruits of their labour, and that therefore all natural rights are invalid because they are all created and defined by the state.

All this confusion could have been prevented if only someone had pointed out to her that copyright isn’t a natural right (and claims over the years that it is have been debunked a few times even in court).

She wouldn’t then redundantly conclude that “A relational theory of copyright thus repudiates any notion of copyright as a natural right of the author”.

I guess she never stopped to consider why a right would be called ‘natural’ if it was something created by the state.

It is further evident that Carys Craig has swallowed the pretext that copyright truly is the state’s mission to incentivise authorship on behalf of the public, and its current form as a reproduction monopoly merely represents its best attempt to do so.

This book is the sort of thing that could have been written by an enthusiastic drinker of copyright Koolaid, i.e. someone who dearly wants to help the state better achieve what they believe is its philanthropic mission to foster our cultural discourse – copyright’s apparent objective.

Oh dearie me.

I don’t know if I can face chapter 4.

4. Against a Lockean approach to copyright

Carys Craig suggests that copyright can be conceived of as a triadic relationship between author, the intellectual work, and the public. However, she bandies the copyright term of ‘protection’ around without reference to precisely how an author’s work is protected (and from what), and seems to believe this is protection of the ownership of the published work as the author’s rightful property. Copyright’s history as a reproduction monopoly destined for exploitation by the press, where it is the monopoly that is protected by that privilege, at the holder of the privilege’s expense (invariably not the author), is omitted from this relationship.

It’s a much simpler relationship that can be expressed without copyright:

- Human being speaks speech to others.

- Individual communicates with other individuals.

- Writer writes writing for readers ready to read.

- Author produces a novel for communication to the general public.

- In exchange for a commission, an intellectual worker produces and delivers intellectual work to their commissioners.

Copyright is an alien interloper wholly unnecessary in such a simple relationship.

If there’s any triadic relationship due to copyright it’s between the privilege holding press, the privilege granting state, and the ever increasing corpus of privilege ‘protected’ works.

In order to have an enriched and consequently beholden press to quell seditious propaganda in the state’s interest, the state grants a reproduction monopoly to arise in all ‘new’ cultural works – at the expense of the public’s cultural liberty (the annulling of the individual’s natural right to copy or communicate the cultural works in their possession or those communicated to them). That the author is the initial holder of a work’s copyright is a mere logical necessity – though a very convenient pretext to pretend as copyright’s raison d’etre. The other pretext is that being obliged to pay authors (as little as possible) for transfer of their monopoly to the press this thus ‘richly’ rewards and incentivises authors to write that which no-one else would otherwise commission, and so therefore amply compensates all authors and readers for their loss of liberty in being able to copy, perform, adapt, translate, or build upon their own* or any other author’s published work, and compensates for the high, monopoly-protected pricing of a non-free market in such.

*

Yes, copyright even annuls the author’s right to copy their own work – though they may (if they can afford it) retain the privilege or a license to do so. Carys Craig seems attached to the notion that copyright is a right of the author, and not the privilege of the holder.

Just as she mistook copyright for a natural right, Carys Craig then proceeds to mistake copyright as justified by Lockean labour theory. She seems completely blinded to see the monopoly as the natural property right, when it is nothing of the sort, but a state granted monopoly. Of course an author has a natural property right to their intellectual work, just as they have a natural property right to their material work, e.g. in weaving a basket. But the state does not grant them a monopoly in their baskets that no-one may make copies of a basket they purchase. Without copyright, an author naturally owns the words they weave into writing as much as they’d own the reeds they may weave into baskets. But, without copyright, an author has no power to prevent others making copies of their writing, just as they have no power to prevent others making copies of their baskets – ONCE they’ve given them to others or exchanged them with others.

Locke deprecated the monopolies enjoyed by the Stationers’ Company and it does his name a disservice to suggest that there exists a Lockean justification for copyright.

Carys Craig further consolidates the idea that copyright is the right of the author, not the privilege of its holder. And she also can’t help but repeat the myth that copyright’s purpose is ‘to promote progress in the science and useful arts’. The US Constitution never actually made any statement concerning copyright, despite the canard that it did. “to promote progress in the science and useful arts” states the consequence of the Constitution’s empowering of Congress to secure to authors the exclusive right to their writings (not the consequence of Madison granting copyright for the benefit of the press). Note that this section of the Constitution does not empower Congress to grant the privilege of copyright nor any reproduction monopoly, but it DOES empower Congress to grant Letters of marque and reprisal. Power to secure a right is categorically different from power to grant a privilege, and the latter is not implicit from the former – though it seems Madison found this possible when he later re-enacted the Statute of Anne for the benefit of the US press.

By the end of chapter 4 I’m beginning to suspect that Carys Craig is misrepresenting natural rights as copyright’s justification in order to discredit them and undermine any reference to natural rights as justification for copyright’s abolition. Why else does she persist in the doublethink of holding copyright as a natural right simultaneously with the recognition that it is a privilege created by the state?

Carys Craig must either wrongly believe that Locke posited that baskets forever remain the uncopyable property of the weavers who wove them, or Carys Craig must recognise, as Locke did, the difference between property and a state granted reproduction monopoly. I fear Carys Craig is leaning toward the former.

At least Carys Craig has introduced me to the astonishing news that there exist some people who believe copyright is both a natural right, and that it can be self-evidently recognised as such allegedly according to Lockean labour-acquisition theory (despite being the most complicated and poorly understood law ever to appear and remain on the statute books).

5. The evolution of originality: The author’s right and the public interest

Carys Craig wastes everyone’s time on a wild goose chase in pursuit of originality. This is beating about the bush of:

- Originality for the purposes of copyright is that which can be protected by copyright and via provenance isn’t (or hasn’t been) already protected by another copyright

Copyright isn’t about rewarding originality, it’s about protecting a monopoly. Originality is merely an alternative term for ‘that which is not already protected’. It is a simple consequence of logic that one monopoly cannot protect that which is already protected by another.

Interestingly, copyright is limited to a monopoly over reproduction by provenance, not by similarity (much as many assume). This means it is possible for what appears to be the same work to be protected by two different copyrights.

For example, what happens if two authors, one in the north of a country and one in the south, both coincidentally produce and publish an indistinguishably similar limerick? Both limericks, both being original, are both protected by copyright (neither is a copy of the other). Do the two copyrights collapse into a shared copyright? Or must every copy and derivative of each be careful to demonstrate its lineage? What if one copyright holding author is a laissez faire liberal happy to see their work proliferate naturally among the people and the other has transferred their copyright to a highly litigious publisher? Such are the conundrums that result from unnatural legislation.

6. Fair dealing and the purposes of copyright protection

“I hope to show that a property rights-based model, which focuses on the individual author-owner and overlooks the dialogical nature of expression, is not equipped either to respond to the needs and interests of users or to reflect the importance of downstream, derivative uses of protected works for society”

Firstly, copyright is a privilege that focuses on the corporate holder of our natural right to copy, which by its very purpose doesn’t so much overlook ‘the dialogical nature of expression’, but deliberately abridges it in order to create a monopoly over reproduction or communication of specific works.

Secondly, in terms of mankind’s culture, human beings are not to be relegated into mere users or consumers of ‘protected works’ but must remain recognised as freely communicating individuals – however much this undoes 18th century privileges. Shakespeare was not a ‘derivative’ user of protected works, but well read, culturally fluent and eloquent to boot. He needed no copyright, nor did those he read or derived from, nor did those who read or derived from him, though his printers may well have cherished any printing monopoly they could convince a king to grant them.

Although a monopoly can certainly be a lucrative instrument of commerce, it remains an instrument of injustice. It is not necessary to culture, nor to commerce, but it is of course nonetheless attractive to those who can obtain it. At some point in our state education system we are taught that a weaver who copies and sells another weaver’s basket is a competitor to be praised, but a printer who copies and sells a another printer’s book is a competitor to be imprisoned. And we are taught that this is nothing to do with the history of the printing press and the lucrative privileges granted to it, but the need to remedy nature’s failure to imbue authors with the power to prevent others printing copies of the books they publish, singers with the power to prevent others singing the songs they sing, comedians with the power to prevent others retelling the jokes they tell, fashion designers with the power to prevent others copying the dresses they sell, and shipwrights with the power to prevent others copying the hull shapes they develop (whereas weavers have to make do with selling their baskets in a free market rife with competition).

I remain surprised that Carys Craig maintains that copyright was created for the benefit of society rather than the press (and crown).

Chapter 6 starts off by reviewing fair use/dealing – discretionary ‘wriggle room’ provided to enable judges to deem infringements they consider benign as ‘not infringing’, but which is often sadly mistaken as a clearly defined set of acts concerning any covered work to which people retain their natural liberty. It seems that Carys Craig buys the idea that, re-conceptualised, fair use/dealing “allows the copyright system to advance the public interest in the creation and exchange of meaning, and not simply to guard the rights-bearing author against every unauthorised use”. Yeah, right – if you can afford a lawyer (as Lessig says).

Pretty much all the discussion on fair use/dealing amounts to a confusion between the individual’s obvious need of their natural right to copy (for research, cultural engagement, etc.) and the copyright holder’s interest in it remaining annulled so they can commercially exploit the reproduction/communications monopoly. The vastness of copyright law and books about it is primarily a consequence of this confusion and inherent conflict between the individual’s liberty and the privilege that annuls it (and the insistence on using the term ‘right’ for both). Carys Craig won’t shift paradigms (and write less verbose books) until she ends the doublethink that the 18th century legislative accident known as copyright can continue to coexist with the individual’s natural right to copy that preceded it, continued as ‘piracy’ in spite of it, and will remain after it.

Discussion of fair use/dealing segues into the snake oil that is ‘digital rights management’ and the laws (DMCA, EUCD, C-11, etc.) enacted to persuade people that such DRM ‘technology’ actually works (via punishments that underline that persuasion). Of course, goes the thinking, if people can be pretended to have only controlled access to a copyright protected work, whilst not actually being in possession of a copy, then they can’t even claim any need to make copies that might have fair use/dealing defences – since they have no copy from which to make any further copies.

Carys Craig comes to a rather feeble conclusion – failing to recognise that the DMCA and its ilk come from the same stable as copyright itself – that of the mercenary monopolist, not of the cultural philanthropist.

7. Dissolving the conflict between copyright and freedom of expression

Apparently this chapter is “concerned with the relationship between freedom of expression and copyright law, and more fundamentally, with what this relationship – its conflicts, tensions and purported resolutions – can reveal to us about the nature of the copyright interest”. It sounds promising, but something tells me Carys Craig will fail to recognise the elephant she’s been feeling her way around in all the preceding chapters and conclude that there is no conflict between the individual’s natural right to copy and this 18th century privilege that annuls it (after all, she thinks copyright is a natural right – god knows what she thinks ‘freedom of expression’ is).

Perhaps, Carys Craig wonders, “an absolutist conception of the right of free expression [oh, it’s a right now is it?] could render the Copyright Act unconstitutional. But then, as Nimmer reminds us, the ‘reconciliation of the irreconcilable, the merger of antitheses … are the great problems of the law’”.

Well, yes, legislators need a lot of veneer and PR spin to persuade the populace that the iniquitous privileges that abridge their liberty are not in conflict with it, but indeed enhance it. James Madison could not actually empower Congress to grant the monopoly of copyright, but he had a damn good try, and as it happened, hardly anyone noticed that instead of enacting law to secure the individual’s natural exclusive right to their writings, he simply re-enacted the Statute of Anne to rubber stamp the monopolies that the press in some states had already decided they needed. Strangely, US patent law was not against people copying each other’s designs, but doing anything similar. It’s funny how two monopolies can be so different when notionally sanctioned by the same Constitutional clause. It should be obvious why Madison declined Jefferson’s suggestion to explicitly grant monopolies “Monopolies may be allowed to persons for their own productions in literature, and their own inventions in the arts, for a term not exceeding ___ years, but for no longer term, and no other purpose”. Just we today pretend monopolies to be a right, so Madison preferred to infer from ‘power to secure a right’ the power to grant monopolies. An author’s or inventor’s privacy is a natural right (the natural boundary and power to exclude others from seeing or copying their private writings or designs). The privilege of a monopoly, a grant of power against competition, is neither a right nor its securing, but then who cares?

There’s a wee misunderstanding on page 205: “Individual B has the right to prevent A from copying expression substantially similar to B’s copyrighted expression”. Copyright is based on provenance not similarity – irrespective of similarity being used to determine whether copying is likely to have taken place. Of course, in practice, copyright being the privilege to threaten, it doesn’t matter whether an alleged infringement is a matter of similarity through coincidence or provenance.

Carys Craig ultimately fails to disentangle copyright’s supporters’ conflation of the monopoly with the author’s property right. Of course, speech and intellectual works can be physically fixed and bounded and can constitute property, but property is property. Property is not a monopoly that prohibits others from manufacturing copies/imitations of the property they purchase. Yes, copyright as a transferable privilege is a form of legal property, but in that context it is the privilege that is property, not the intellectual work it ‘protects’.

Failing to resolve freedom of expression with its constraint at the hands of the privileged, this chapter concludes, as I suspected it would, by restating the doublethink that “Only by giving sufficient consideration to the public interest that underlies copyright, and by recognising the social values that provide its foundation, can we appreciate the limited nature of the copyright interest, and the room it must leave for the ongoing generation and exchange of meaning”. With that paean to Queen Anne’s putatively philanthropic prerogative Carys Craig flagrantly ignores the monopolist behind the curtain as she serves us her saccharine jugs of ‘Copyright is good for our culture’ Koolaid.

8. Final conclusions

After seven tedious chapters, Carys Craig ends with a damp squib. She has nothing concrete to offer, and can muster at most a recommendation that there is a re-imagination of copyright as something to “facilitate the generation and exchange of intellectual expression such that nobody is denied the right to speak as well as to listen, to respond as well as to receive.”

She adds that “The good news for lawmakers is that this re-imagination, however radical it may appear, is easily within their grasp.”

Carys Craig thus displays her apparent belief that mankind’s laws are made by lawmakers, not mankind’s nature, and that with a mere modicum of imagination, the philanthropic aspirations she presumes Queen Anne had for her Statute can be achieved by legislators quite easily – presumably, if only they would let their imaginations loose and stop thinking in terms of the author’s presumed right to control the use of their published work (she still thinks of copyright as an authorial right, not as a monopoly intended for exploitation by the press).

“Thus reconceived, the protection that copyright grants to creators of intellectual expression is one means by which the State attempts to stimulate social engagement, dialogic participation and cultural contributions, all of which are aspects of the public good inherent in participatory community.”

Amen.

The book is subtitled “Towards a relational theory of copyright law” and appropriately so. There is no well defined theory here. There’s just a vague conjecture that there could be one and that by thinking of copyright with a less proprietary mindset one might move toward it.

Carys Craig’s book does the monopolist manifesto no favours. The most it accomplishes is a demonstration of the contortions a copyright apologist must put themselves through in order to argue that copyright might conceivably be made into the equivalent of its own abolition.

This book could be more coherent if rewritten – for an audience of readers in an alternate universe in which the privilege of copyright had never been granted. However, the only thing that such a book could present as possibly appealing to such an audience is a monopoly’s lottery prizes to the few (and the revenue to the corporations that administer/exploit it). One cannot offer a society used to cultural liberty the benefits of being prohibited from sharing or building upon its own culture of published works. Copyright is something the state enacts as a fait accompli first and finesses as an essential benefit to its people afterwards.

If Edward Elgar should be rewarded to the tune of £65 per copy for publishing any of their books, I suggest it’s “Rethinking Copyright” by Ronan Deazley. If you would reward Carys Craig for her work, I suggest you send that book to her after you’ve read it (that way she’ll presumably get £65 worth of a copy of an intellectual work, as opposed to a typically minuscule royalty if you bought hers instead).

“Copyright, Communication and Culture” by Carys J. Craig is published by Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

A is for Abolition

When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.

We must abolish copyright.

This is a conclusion anyone can avoid coming to – if they covet copyright’s corrupting power to constrain all others.

B is for Building

Build upon my published work!

Build upon everyone’s published work. You are naturally at liberty to do so.

C is for Copying, not ©

Copy and communicate all published works, yours, mine, everyone’s – to the far corners of the earth.

D is for Derivatives

See Originality.

Nothing is new under the sun. Nothing is 100% original. Everything is derivative in some way. Mankind progresses by building upon what has been done before – through exploration and improvement. There is no wrong in this. Develop derivative works of your own, however similar or dissimilar to those you’ve been inspired by.

E is for Enjoyment

Enjoy your natural liberty. Enjoy your own culture. Enjoy sharing in it with your friends. Enjoy sharing it with everyone!

F is for Funding

Feel free to fund my further work if you fancy more. Feel free to fund any artist whose work you would have more of.

Pay others for what you cannot or would rather not do yourself. Pay artists for their art. Pay printers for prints. If you can make your own copies and prefer to, do so. Ignore any state granted monopolies that prohibit such liberty.

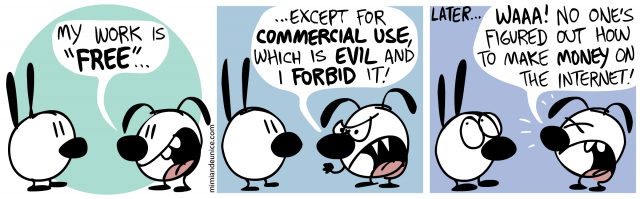

Liberty does not mean artists work for nothing, even if monopolists may not profit so much. Even so, it may sometimes be prudent to give your work away to promote yourself, to win fans, and future funding. Free as in free speech, not as in free beer.

Copying is not a crime, nor does it pilfer pennies from the pockets of the poor – except in the eyes of those who covet copyright.

G is for Gutenberg

Gutenberg started the printing revolution. The Internet put the revolution into hyperdrive.

18th century privileges designed to quell sedition and piracy are running on empty.

Project Gutenberg is helping to demonstrate that paying authors to write novels is not precluded by ending the practice of purchasing books from those privileged by a monopoly or paying them for permission to print copies.

Copyright is a brake on the wheel of the communications revolution. Only the corrupt few can profit from the energy they sap, even as so much progress is lost as a consequence.

Set us free. Set our culture free. See how much faster we go.

H is for Honesty

Honesty is a moral obligation.

While you are at liberty to use any published work as you see fit, such liberty naturally excludes dishonesty, e.g. misattribution or misrepresentation.

As credit is a gift, and citing sources is a mark of respect (though fraught with peril today as it risks inviting copyright litigation), so appropriate attribution is up to you. A lack of attribution is not a priori dishonest. You have no moral obligation to provide attribution, but neither deceive your audience, nor be so neglectful that you cause confusion in this respect.

Misrepresentation would be where you might use an artist’s work in a way such that others are likely to incorrectly infer the artist endorses a product or political point of view.

It is in this aspect that moral rights can be identified and enumerated. Unfortunately, they tend to be corrupted by copyright-based thinking into yet another set of proprietorial privileges. For example, your moral right to integrity is not the power to veto changes another artist may choose to make to your published work, but the other artist’s moral obligation not to misattribute the changes they are at liberty to make to your work as yours, or authorised by you. It is a matter of truth, not of power over others (granted by the state).

I is for Intellectual Property

Intellectual work may be property, but copyright is an unnatural monopoly.

The intellectual work contained within the unpublished manuscript in your desk drawer is undoubtedly your intellectual property, but if you sell or give it to someone, or a copy thereof, it becomes their property – even if it is not their work.

The reproduction monopoly arising in an ‘original’ work, granted by the state, that empowers the copyright holder to sue infringers, is unnatural, nothing to do with property (except in attempts to corrupt the term), and hence an unethical derogation of an individual’s liberty – to copy or communicate that which they’d otherwise be at liberty to.

J is for Justice

Justice is expected through the instrument of government, but its privileges are instruments of injustice.

K is for Kickstarter

Kickstarter and other such marketplaces enable artists to exchange their work for money, not a state granted reproduction monopoly for a pittance from a publisher plus their over-hyped possibility of the ‘lottery prize’ they call royalties.

These marketplaces will become more numerous, more sophisticated, and will represent a return to the pre-copyright method of funding. Instead of monopoly profits, a few patrons, or millions of fanatic micropatrons, or simply, fans, will offer funds in exchange for the artist’s art. Art for money, money for art.

It’s not simply ‘give it away & pray’, whether giving away your art to your fans, or giving away your money to your favourite musicians, but as in any market, it’s about coming to an agreement, an equitable exchange.

Don’t forget though, caveat emptor and caveat venditor still apply.

L is for Learning

Learn is from leornian – to tread in another’s footsteps, to copy another’s path.

But, as modern dogma has it, ever since Queen Anne first let slip the pretext that copyright would result in the Encouragement of Learning, we will be more encouraged to learn from each other because we are prohibited from copying each other.

The first question that should spring to mind is “What kind of law is it, that must be preceded by an unfalsifiable excuse?”. What other law, whether it be against theft, violence, kidnapping, or fraud, must have its enactment preceded by a claim that it will be for society’s benefit?

Even copyright’s fiercest critics still accept its pretext, that its purpose is philanthropic, and that the privilege may continue to be judged upon its mythical benefit to society, despite the fact that we have not witnessed the supposedly dystopian society that has long existed with printing, but without the alleged benefit of a privilege prohibiting piracy on its statute books.

How do we know we are benefiting from copyright if we’ve never known what our culture could have become without it? How does a slave know they are benefiting from their master’s care if they’ve never known what it’s like to find employment in a free market? It’s not a matter of benefit, alleged or imagined. People instinctively recognise the liberty they are born with, and are driven by the imperative to exercise it. If some want to pretend they must ask permission for their liberty, that a need to obtain such permission benefits them, then let them indulge in such a pretence, but do not let the state visit such injustice upon all.

If you look into copyright, if you dare question its pretext, then you should learn that its origins were entirely mercenary, in the interests of the state – and the press it would have beholden, and obedient to it.

That copyright encourages our learning, and feeds poor starving authors to so enlighten us, is a fairy tale once told by a wicked queen, and her successors for three successive centuries.

If we all dare admit the empress is naked, her empire ends.

M is for Monopoly

There are three notorious state granted monopolies: Copyright, patent, and trademark. Each monopoly differs somewhat in its concern and modus operandi, however, whilst some may claim they protect natural rights they are wholly unnatural, being unethical privileges enacted for the benefit of the state and the enrichment of those who lobby for them.

Copyright is not designed to help the individual author against the theft of their unpublished manuscript. It is a monopoly provided for the wealthy and powerful publisher to police the marketplace against competition (pirate printers). Contrary to dogma, it does not encourage learning.

Patent is not designed to help to the individual inventor against the theft of their unpublished invention. It is a monopoly provided for the wealthy and powerful manufacturer to police the marketplace against competition (especially foreign). Contrary to dogma, it does not encourage innovation.

Trademark is not designed to help the individual against passing off by unscrupulous competitors. It is a monopoly provided for the wealthy and powerful merchant to police the marketplace against competition (better value for money imitations). Contrary to dogma, it does not protect the public against fraud.

N is for the Nature of Rights

If copyright encourages anyone to do any learning, it’s learning about copyright, learning about its origins, learning the reasons for its injustice, learning about rights, what they are, where they come from, whether they can be granted, bought, sold, or taken away, and who by, e.g. gods, queens, governments, ourselves, mother nature, or accident, etc.

Thomas Paine has written about rights, as have others over the millennia preceding copyright. Obviously, those interested in continuing to enjoy copyright, ‘The Copyright Cartel’ we might call them, have also written about rights – in these last few centuries since 1709.

Depending upon whose writing you read, you will either learn that it is your human right to prevent others making unauthorised copies of your published work, or that it is a right granted by Queen Anne, that may be bought, sold, assigned, licensed, reserved, waived, or any manner of other things. You will also learn that copyright is a good thing, or that it is a bad thing, or even that it is a ‘necessary sacrifice’ for the greater good.

If you don’t want to risk shifting paradigms, and prefer the comfort of ignorance, then stick to the dogma you thus know and love. If you realise there are problems relating to copyright, and want to know whether those problems are with the people who disobey it or the privilege that is used to prosecute them, then learn on.

I’ve written about rights before, recently, and may well do so again soon.

O is for Originality

See Derivatives.

Thanks to copyright’s inculcation, originality may now be a common artistic aspiration, and something copyright lawyers will pretend happens every day, but it is unobtainable. The idea that it exists can be legislated, but then the law is an ass, made so by asses. Of course it shouldn’t be legislated, nor should we wish it to be.

Further reading: The Perfectly Acceptable Practice of Literary Theft: Plagiarism, Copyright, and the Eighteenth Century

P is for Privacy, not Piracy

Privacy is the root of property, and the only natural right an author has to exclude others from their work. One cannot both publish and remain proprietor. In other words, one cannot include AND exclude someone. You cannot tell someone something AND deny them their liberty to tell it to others – much as you might covet such a power.

Predictably, publishers pretending proprietorship will perforce pejoratively proclaim as pirates those folk who would enjoy their natural liberty to make and distribute copies or derivatives – contrary to the usurping proprietor’s presumption of propriety.

Daniel Defoe was there at the beginning of both copyright and piracy, and may even have some posthumous resonance at their ending: shipwrecked in a pirate bay, and naming a party of pirates campaigning to cease copyright’s punishment of individuals who engage in fileharing.

I refer of course, to The Pirate Bay, and The Pirate Party. These are harbinger’s of doom, both for the privilege of copyright, and the idea that those who ignore it are delinquent pirates.

Q is for Queen Anne

Queen Anne established the privilege we call copyright in 1709 – the root of all laws that prohibit one person from copying another. From 500,000BC to 1708AD, Homo Sapiens developed into a civilisation through copying, learning, and improving upon each other’s work. From 1709 onwards, we suffer the legacy of a legislative misadventure, a privilege that should have been abolished along with slavery, not one that should have been re-enacted in 1790 by a government supposedly created to secure its citizens’ liberty and the ending of monopolies (such as established by Britain’s Tea Act).

R is for Reform

Reforms of copyright are generally proposed by those engaged in doublethink – that it is possible to have a monopoly and cultural liberty.

One of the most popular kinds of reform is that of term reduction. This is presumably based on a supposition that if copyright only prohibited the copying of a work for a decade or so, as opposed to a century or so, that people would be more likely to respect the 18th century privilege, obeying it, than to disrespect it, ignoring it.

Piracy has occurred before, and where the state has realised copyright is too clumsy or ineffective (but never unjust), it has introduced compulsory licensing. There are those who suggest this applies to the Internet, and so a compulsory license fee (or mulct) should be levied upon all who use it, to be disbursed to poor starving artists (aka publishing corporations and collecting societies) according to the proliferation of their work. This idea for reform has not gained much ground because no-one has yet figured out how to accomplish it without making it easy for people to see that 99% of the mulct ends up in the pockets of corporations rather than individual artists. Further reading: The nature of intellectual property in the mid-twentieth century

There is, as it happens, one reform of copyright that does make it possible to have a monopoly and cultural liberty. This is where individuals (persons born with liberty) are exempt from copyright, but corporations (artificial entities unethically recognised as persons by law) are not exempt. So, human beings enjoy their natural right to liberty, and corporations enjoy the monopoly they so enthusiastically lobby for.

Generally, copyright reform is a conceptual trap, a means of lumping together those who’d abolish copyright, with those who’d change or replace it, with those who’d extend and enhance it. Reform is always on the cards. The state will get round to listening to people’s concerns in due course – invariably producing legislation that panders to the concerns of the incumbent powers, not those of the subject populace, e.g. The UK’s Digital Economy Act

If you campaign for copyright reform, at best you campaign for nothing, but the status quo, at worst, for the ratcheting up of that which concerns you. Obviously, if you support copyright, ‘best’ and ‘worst’ should be interchanged.

S is for Software Freedom

Software engineers, notably Richard Stallman and the copyleft movement, have helped demonstrate that copyright is socially counter-productive and uneconomic – however lucrative to the few monopolists in a position to exploit it.

Unfortunately, copyleft has also created a perverse dogmatism that the privilege of copyright is necessary for software freedom. I try to present the arguments against this misunderstanding in Copyleft Without Coercion.

T is for Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine provides a good understanding of natural rights, and helps explain why privileges that annul natural rights in the majority (such as our right to copy) in order to leave them, by exclusion, in the hands of a few (copyright holders), are consequently instruments of injustice.

Also see Thomas Edison’s commendation The Philosophy of Paine

U is for University

Universities are supposed to produce and disseminate mankind’s knowledge, not to hoard and guard it, martyring those who would disseminate it – such as Aaron Swartz.

Are you really sure copyright encourages our learning?

V is for Value, not Vendetta

Value is subjective, but don’t confuse the value of the work with the value of the copy. Artistic work is typically expensive and highly skilled. Copies are typically so inexpensive and easily produced that machines can make them by the million.

Pay artists to produce art. Pay printers to produce prints. But for your liberty to make your own copies, pay copyright holders nothing but contempt.

If someone has copied you (without dishonesty/plagiarism), or is selling copies of your work, they are promoting you and to be praised, not to be punished or otherwise persecuted – however much power to do so you imagine copyright says you deserve. Value the contributions of others, don’t be vindictive against them, nor wage vendettas against those the demon of copyright is persuading you are unfairly profiting from your hard work.

W is for Work

Work does not constitute entitlement to payment. One must find those who want the work done, who would pay for it. Being paid for your work is about finding an agreeable, equitable exchange in a free market. Your right is to be at liberty to do so, not to abridge the liberty of others to do so – who may be paid to add value to your work or build upon it.

X is for Xerox

Xerox marked the spot at which making one’s own copies became cheaper than buying them, the moment at which the fate of the 18th century reproduction monopoly became sealed.

Y is for You

You are naturally at liberty to copy – that which you have found, that which you have been given, or that which you have bought. Your natural imperative is to share and build upon your own culture – to ignore copyright. Your natural power and right to copy is in your own hands. That you have been fooled to believe it is instead in the hands of a copyright holder is within your power to remedy. You must snap out of this delusion.

Z is for Zygote

The zygote is a clue that copying and derivation is so much a part of nature that it is essential for the progress of life itself. To copy is in our genes. To copy is human.

That a prohibition on copying, the abridgement of our liberty, is necessary for mankind’s learning and progress, is the lie of all monopolists corrupted by power, from Queen Anne and James Madison to The Estate of Martin Luther King.

Whereas slavery takes all liberties from a few, copyright takes a few liberties from us all.

Learn about liberty, your liberty to learn through copying, your cultural liberty.

The abolition movement continues…